Under the Gun: “Hacking” Out Braille-on-Demand in 24 Hours

When six students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) decided to enter a “hackathon,” they had no idea they were going to invent a cutting-edge technology that would become a career focus for many of them. Team Tactile entered “as a team of friends just for fun,” but won first place for their text-to-braille converter, Tactile. “Surprisingly—shockingly—we learned that there was nothing like this already on the market,” says team member, Charlene Xia.

A “hackathon” is a 24-hour invention competition in which teams make something using sponsor-supplied materials. While brainstorming the eve of the event, Team Tactile saw a braille watch among the inventions they were browsing for inspiration, and began to research ways to improve the concept. “We thought maybe we could generalize this idea even more—instead of just helping the blind to tell time, maybe we could do something broader, like convert text to braille in real time.” Their idea was bolstered by the team’s Chandani Doshi, who had once worked at a school for the blind. “She knew the pain points of students who are visually impaired and the challenges they face trying to access information; she really drove the impact aspect of the project and helped to get us all on board,” Team Tactile member Julian Shi says.

Since winning, Team Tactile has worked with Microsoft’s #MakeWhat’sNext program to patent and commercialize the product. This program is an endeavor that “seeks out industrious groups that include at least one female member, who are advancing technology that could make a real difference.” The program links the inventors with Microsoft patent lawyers and a Patent Board of senior company leaders, researchers, and technology experts to provide guidance. At least three Team Tactile members will pursue Tactile full time after they graduate.

Innovator Insights spoke with the team to learn more how they are working with Microsoft to ensure their invention is available to all those who are visually impaired.

How did Team Tactile meet?

We met freshman year. We’re all seniors now and have different majors, but we became really close friends.

Were you all always interested inventing?

Tactile is the first invention that any of us worked on. We had all tinkered with other ideas before, but nothing like this.

One thing we have in common is how supportive all of our parents were of our interest in science and engineering. They encouraged us to play with science-themed toys and never made us feel like we had to like toys deemed more suitable for girls, for example. Having that confidence and encouragement at a young age played a big part in each of us pursuing this path.

How does Tactile improve upon the current technology?

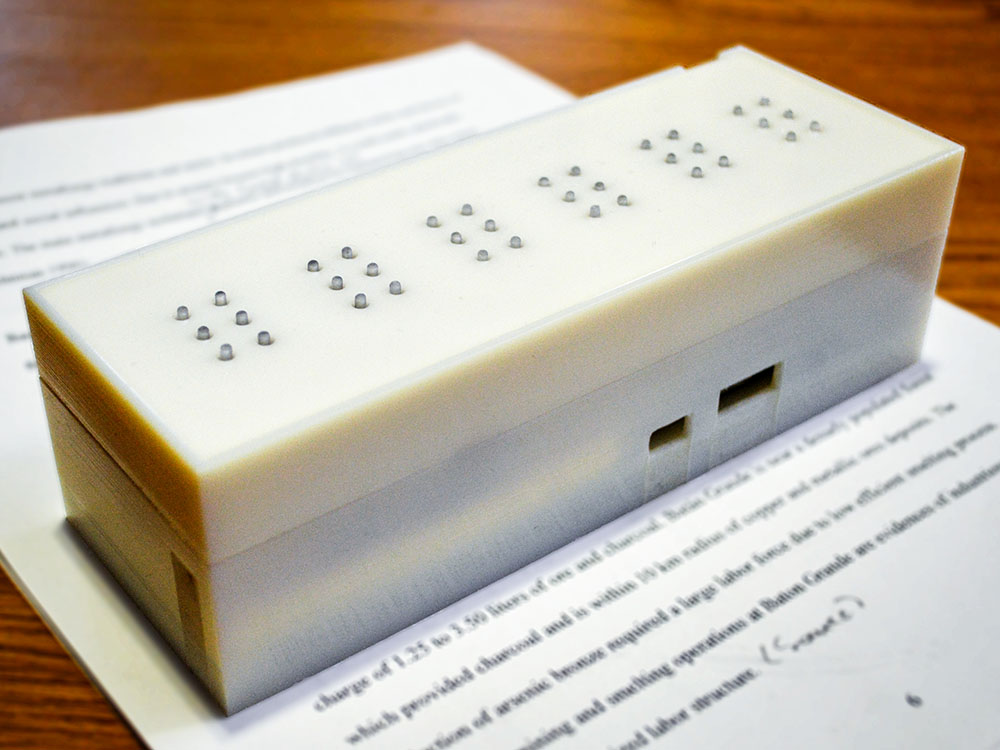

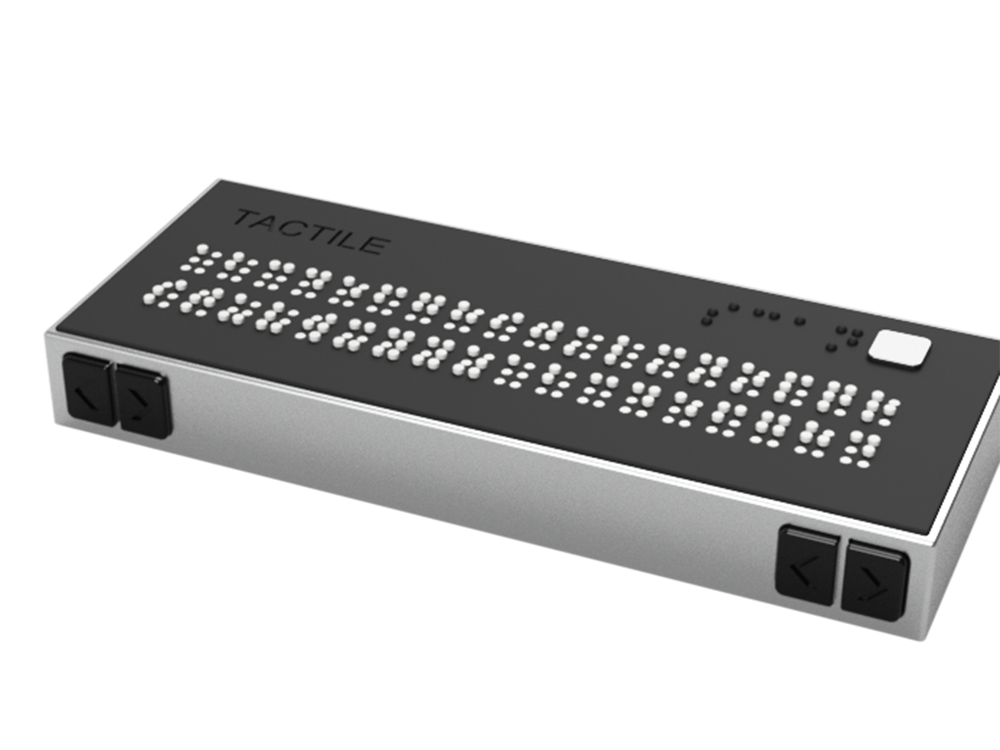

What’s currently on the market is a “refreshable braille display,” which allows someone to read text on a computer in braille, but Tactile actually offers “braille-on-demand.” Tactile is a text-to-Braille portable device that can scan any printed text and convert it to braille.

First, we aim to develop a refreshable braille display using electromagnetic actuators that is cheaper and more compact than existing refreshable braille displays. Tactile is placed on top of a block of text. The device has embedded cameras that take images of printed text. The printed text is converted to digital text using Microsoft’s optical character recognition software, then translated and displayed on the braille display.

The challenge with image capture is alignment. Someone who is visually impaired can’t know if they’ve placed Tactile in the right orientation. We make that process simpler using an intuitive design where a person can align Tactile with the edge of a page. We will create a controlled image capture environment so the picture is always in focus and well lit. We will also incorporate feedback to the user if more adjustment is needed.

How successful was your prototype?

Having that confidence and encouragement at a young age played a big part in each of us pursuing this path.

The hackathon was very hectic, but within 15 minutes of deadline we had our first prototype. It was very slow—it could only display one letter per second—but when we presented it to the judges we conveyed our larger vision and they were very receptive. We came in first place.

Are you in the process of patenting it?

With the help of the Microsoft #MakeWhat’sNext program, we filed our patent application. We’re waiting to hear back still, but we have patent pending status.

How did you become involved with #MakeWhat’sNext?

A piece of our text recognition software uses Microsoft software, so through the hackathon we got in touch with the Microsoft sponsor and he referred us to this program. We’re part of the pilot phase of the program. It’s great, because we had thought about getting a patent, but we never knew how complicated it was. We initially went to MIT and they said there was good news and bad news. The good news was that we’re undergrads, so we retain the rights to anything we invent at MIT. The bad news was that they couldn’t help us to file for a patent unless we would let them retain some rights. We were kind of stuck because none of us had the legal expertise to navigate or funds to pay for lawyers and fees. Microsoft covered all of that.

Did any of you know much about patents before this?

In high school we talked about the history of patents, but not how to apply for one. We learned about the history of scientists and inventors, but never the nitty gritty of what the patent process is like. When we got to MIT, we learned more about patents in a course that we took on how to apply for a patent and what they can do for you. We learned that it’s a complicated field and there are a lot of different approaches, so it was kind of intimidating. I don’t think we ever thought we’d one day get a patent ourselves.

There is sometimes criticism of the patent system, especially in relation to technology for the sick or disabled—have you encountered any of that?

I think MIT has a different view because the school is so research focused. Patents are viewed very positively here. People see patents as proof of accomplishment, not so much as a tool to keep people out of your invention. A patent is a validation of your work. It’s almost equivalent to publishing an academic paper.

It’s a difficult question, because the patent protects the inventor. It’s their idea, and you should give them a fair chance to do as much as they can with it before people can just copy and run with it. At the same time, ideally the inventor shouldn’t be thinking about money; they should be thinking about a project, and at the end of the day, if you truly care about your invention and project you want it to go as far as possible. I feel like there are some IP owners who lose track of what they’re inventing and think too much about money.

What kinds of challenges have you faced during this process?

We’re in a unique spot at MIT because the ratio of women to men in the engineering disciplines here are pretty balanced, but all of our friends going to other engineering schools say that they’re one of the only women in their classes. We haven’t had to face that yet, but now that we’re going to graduate and go out into the field we’re going to come up against reality. Where we intern, for instance, we’re one of the only female teams in the whole engineering department. It makes you feel like you’re different and it’s hard to relate in some sense. We can foresee a situation where, later on after becoming an entity, we might be questioned on our technical competence to finish this project when asking for investment, for instance. One of the things that will help us is being able to say we have an MIT degree, but some might be doubtful because there’s not a single man on our team.

I think schools should focus on naturally integrating STEM programs. There are definitely a lot of clubs and societies for women at MIT, it’s very important for schools to foster a strong community of women in STEM for people who are just coming in to feel supported and to make sure there are strong female role models. We’re lucky to have a lot of strong female professors who we can look up to. The female professors we have at MIT are amazing.

What advice do you have for other young inventors?

People see patents as proof of accomplishment.

I think we would all suggest inventing as a team. It may sound weird, but it’s so helpful to have someone else to bounce ideas off. You can have an idea, but the hardest part is to stay motivated through all of the struggles. If you have a team to back you up and motivate you, that’s really important. If any one of us had done this individually, I don’t think we’d have had as much confidence or reached the level of success we have now.

Also—do something cool. We’ve never thought about making money; we’ve always stayed focused on making something useful. That’s how it should start—as a cool idea that you feel passionate about. That’s how you get the first spark, and then maybe everyone else will think it’s cool too and that’s how it becomes a success.

[ssba-buttons]